33 TA ΧΡΟΝΙΑ ΤΟΥ ΧΡΙΣΤΟΥ ΜΑΣ ΚΑΙ ΑΛΛΑ… 2! “ΤΩΡΑ”!..

1.

Pentagon kongreye sundu, ABD’nin gizli planı deşifre oldu

ABD Savunma Bakanlığının (Pentagon) Başmüfettişliğince Kongreye sunulan rapora göre, ABD, Suriye’de DEAŞ sonrası dönem için terör örgütü YPG/PKK dahil iş birliği yaptığı “ortak güçlerin” sayısını 100 binden 110 bine çıkarmayı hedefliyor.

Raporun, “Suriye’deki Ortak Güçlerin Kapasite İnşası” başlıklı bölümünde ise DEAŞ sonrası dönem için öngörülen faaliyetler arasında “YPG/PKK‘nın büyütülmesi” maddesine de yer verildi.

Raporda, “Suriye’de fiziksel olarak DEAŞ’ın yenilmesi ve odak noktasının örgütün yeniden canlanmasının engellenmesine kaymasıyla, Suriye’deki ortak güçlerin kompozisyonu da değişiyor. Birleşik Ortak Görev Gücü-Doğal Kararlılık Operasyonunun (CJTFOIR) planı, (Suriye’deki) tüm ortak güçlerin yüzde 10 artırılmasına yardım etmek ve tüm bileşenler arasında yeni güçler oluşturmaktır.”ifadeleri yer aldı.

Bir sonraki bölümde, halen 100 bin kişi olduğu belirtilen toplam “ortak güçlerin” sayısının 110 bine yükseltilmesi için çalışmaların yapıldığı kaydedildi.

Rapora göre, söz konusu 110 bin kişiye çıkarılması hedeflenen unsurların 30 binin çok büyük bölümünü “SDG” ismini kullanan terör örgütü YPG/PKK’dan, 45 bini “Yerel İç Güvenlik Güçleri” (PRIFS) olarak tanımlanan unsurlardan, 35 bini de (Rakka, Münbiç ve Deyrizor’daki) “İç Güvenlik Güçleri” (InSF) adı verilen bileşenlerden meydana gelecek.

Raporda, “Yerel İç Güvenlik Güçleri” ve “İç Güvenlik Güçleri” adı verilen diğer iki unsurun, sahadaki güçlerden oluştuğu ve “SDG” ismini kullanan terör örgütü YPG/PKK ile koordinasyon halinde çalıştıkları kaydedildi ancak aralarındaki bağ veya ilişkiye dair bir tanımlama yapılmadı.

TRUMP’IN GERİ ÇEKİLME TALİMATI ETKİLEDİ

Raporda, ABD Başkanı Donald Trump’ın, Suriye’den çekilme talimatı vermesiyle ülkedeki Amerikan güçlerinin sayısının göreceli olarak azaldığı ve bu durumun DEAŞ’ın yeniden canlanmasını engellemeye yönelik operasyonlara sekte vurduğu savunuldu. Bu yaklaşım, “ABD’nin Suriye’den kısmi geri çekilmesi, DEAŞ’ın isyancı hücrelerine karşı eğitim ve ekipmana ihtiyaç duydukları bir dönemde ortak güçlere sunulan desteğin azalmasına neden olmuştur.” cümlesiyle ifade edildi.

HOL KAMPI İZLENEMİYOR İDDİASI

Pentagon’un raporunda, 10 bin kadar DEAŞ’lı teröristin bulunduğu belirtilen Hol kampındaki hareketliliği ABD’nin yeterince izleyemediği, YPG/PKK’nın ise sadece kısmi güvenlik sağlayabildiği belirtildi.

Söz konusu kampla ilgili önerilen çözümün ise kampta kalan kişilerin başka bir yere nakledilmesi olduğu kaydedildi.

Deyrizor’daki YPG/PKK kontrolü gerilimi artırıyor

Öte yandan rapora yansıyan bir başka bölümde, DEAŞ’tan temizlendikten sonra bazı bölgelerde YPG/PKK’nın elindeki yönetme yetkisinin halkta rahatsızlık yarattığı değerlendirmesi yer aldı.

Örneğin, “SDG” ismini kullanan terör örgütü YPG/PKK’nın Deyrizor’da kurduğu sözde konseyin, çoğunluğu Arap olan bölge halkında rahatsızlık oluşturduğu, sokaklara dökülen insanların protestolar düzenlediği kaydedildi.

Raporda ayrıca yerel halkın YPG/PKK’nın Beşşar Esed rejimine petrol satmasını da protesto ettiği bilgisine yer verildi.

2.

Türkiye ‘gireceğiz’ deyince ABD harekete geçti! Skandal hamle

Başta ABD olmak üzere Batılı güçler, Türkiye’nin Fırat’ın doğusuna gireceğini iletmesinden sonra YPG’ye silah yardımına başladı. Sputnik’in haberine göre Suriye devlet haber ajansı SANA, ABD’nin Irak’tan Suriye’nin Haseke ilindeki Kamışlı şehrine silah ve mühimmat dolu onlarca araç geçirdiğini belirtti.

Haberde uluslararası koalisyon güçlerinin, yüklü miktarda silah ve mühimmat yüklü 200 büyük kamyonun Kamışlı kentine geçirdiği belirtildi.

3.

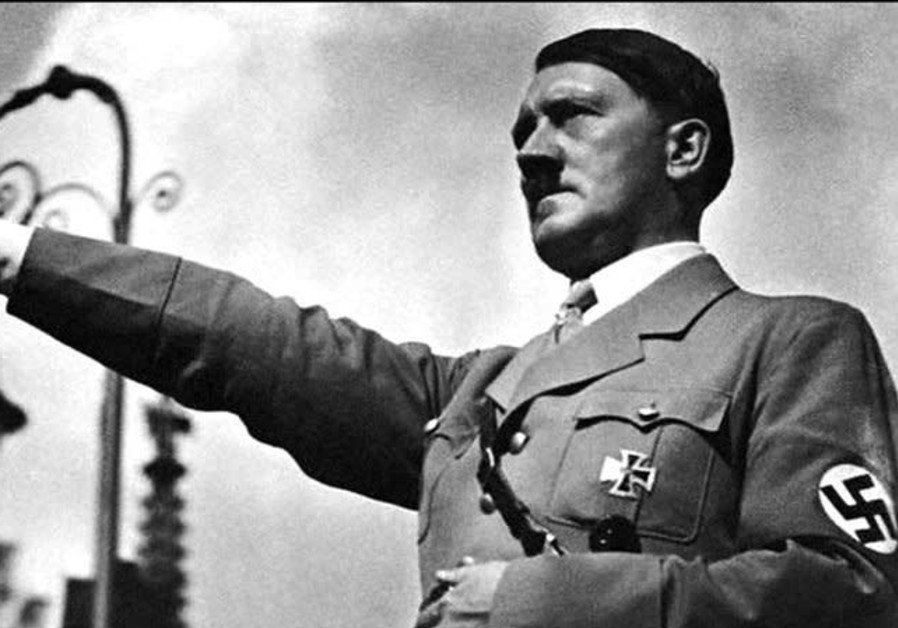

STUDY SUGGESTS ADOLF HITLER’S PATERNAL GRANDFATHER WAS JEWISH

Hitler’s right hand Hans Frank claimed to have discovered that the Fuhrer’s grandfather was indeed Jewish.

Was Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather Jewish?

The controversial theory has been debated for decades by historians, with many agreeing that he was not a part of “the tribe,” as there was no evidence to substantiate this claim.

However, a study by psychologist and physician Leonard Sax has shed new light supporting the claim that Hitler’s father’s father had Jewish roots.

The study, titled “Aus den Gemeinden von Burgenland: Revisiting the question of Adolf Hitler’s paternal grandfather,” which was published in the current issue of the Journal of European Studies, examines claims by Hitler’s lawyer Hans Frank, who allegedly discovered the truth.

Hitler asked Frank to look into the claim in 1930, after his nephew William Patrick Hitler threatened to expose that the leader’s grandfather was Jewish.

In his 1946 memoir, which was published seven years after he was executed during the Nuremberg trials, “Frank claimed to have uncovered evidence in 1930 that Hitler’s paternal grandfather was a Jewish man living in Graz, Austria, in the household where Hitler’s grandmother was employed,” and it was in 1836 that Hitler’s grandmother Maria Anna Schicklgruber became pregnant, Sax explained.

“Frank wrote in his memoir that he conducted an investigation as Hitler had requested, and that he discovered the existence of correspondence between Maria Anna Schicklgruber – Hitler’s grandmother – and a Jew named Frankenberger living in Graz. According to Frank, the letters hinted that Frankenberger’s 19-year-old son had impregnated Maria Anna while she worked in the Frankenberger household: …that the illegitimate child of the Schickelgruber [sic] had been conceived under conditions which required Frankenberger to pay alimony.”

Sax writes in the study that according to the letters in Frank’s memoir, “Frankenberger Sr. sent money for the support of the child from infancy until its 14th birthday.”

“The motivation for the payment, according to Frank, was not charity but primarily a concern about the authorities becoming involved: ‘The Jew paid without a court order, because he was concerned about the result of a court hearing and the connected publicity,’” the letters state.

However, Sax noted that the accuracy of Frank’s claims and his memoir “have been questioned.”

He added that “contemporary scholarship has largely discounted Frank’s allegations regarding a possible Jewish grandfather for Adolf Hitler.”

In the ’50s, German author Nikolaus von Preradovich said he had proved that “there were no Jews in Graz before 1856,” rejecting Frank’s account.

However, Sax explained in the study that he found evidence to the contrary in Austrian archives that there was a Jewish community in the Austrian town before 1850 and highlighted that Preradovich was a Nazi sympathizer, “who was offended by the suggestion that Adolf Hitler was a “Vierteljude (a one-quarter Jew).”

According to Sax’s paper, “Evidence is presented that there was in fact eine kleine, nun angesiedelte Gemeinde – ‘a small, now settled community’ – of Jews living in Graz before 1850.”

Sax also refers to Emanuel Mendel Baumgarten, who was elected to the Vienna municipal council in 1861, “one of the first Jews to hold that honor.

“In 1884, he wrote a book titled… The Jews in Styria: a historical sketch,” in which he states that “in September 1856, he and several Jewish colleagues met with Michael Graf von Strassoldo, who at that time held the post of governor for the province of Styria.

“Baumgarten and his colleagues petitioned Strassoldo to lift the restrictions on Jews residing in Styria,” Sax explained. Baumgarten cited a letter to local mayors in Styria which noted “that Jews are staying in local districts for a long time and are taking up residence for a long time.”

Sax goes on to say that the official register of Jews in Graz “appears to have been launched following this meeting.

Thus, the establishment in 1856 of a community register of Jews in Graz seems not to have been a first step in the foundation of the Jewish community in 16 Graz, as Nikolaus von Preradovich assumed, but rather the recognition of a community already in existence,” he pointed out.

According to a statement accompanying the study, “Sax [also] presents overwhelming evidence that Preradovich was a Nazi sympathizer.

“Sax’s paper shows that the current consensus is based on a lie,” it states. “Frank, not Preradovich, was telling the truth. Adolf Hitler’s grandfather was Jewish.

He added that “no independent scholarship has confirmed Preradovich’s conjecture.”

Οι αλβανικές συμμορίες “παίζουν” τώρα και μέσω του Facebook

Οι Αλβανοί εγκληματίες χρησιμοποιούν το “Facebook” προκειμένου να αποφύγουν τις αντιμεταναστευτικές επιχειρήσεις της αστυνομίας και να φέρνουν παράνομα μετανάστες στο Ηνωμένο Βασίλειο, όπως αναφέρει η βρετανική εφημερίδα “Telegraph”. H σελίδα ονομάζεται «Αλβανοί στο Λονδίνο» και την διαχειρίζεται ο καταδικασμένος, Αλβανός ληστής Τραπεζών, Φάρι Λέσι. Έχει 123.000 ακόλουθους και αναρτά δημοσίως εγκληματικά σχέδια.

Η σελίδα προσφέρει στους Αλβανούς παράνομους μετανάστες «φίλους» της, τα πάντα. Από ειδοποιήσεις σχετικά με συνοριακούς ελέγχους της αστυνομίας, μέχρι φωτογραφίες αστυνομικών και των οχημάτων τους και συμβουλές για το στήσιμο ψεύτικων γάμων.

Μεταξύ των παρεχόμενων υπηρεσιών είναι και η πρόσληψη ανθρώπων που μιλούν Αγγλικά και μπορούν να γράψουν τα “τεστ” που απαιτούνται για τη λήψη Βρετανικής υπηκοότητας ή για την άδεια οδήγησης, αντί των Αλβανών.

Σύμφωνα μάλιστα με τη βρετανική εφημερίδα “Telegraph”, οι διαχειριστές της σελίδας στο “Facebook” την «κατέβασαν» μόλις δημοσιογράφοι προσπάθησαν να επικοινωνήσουν, ζητώντας σχόλιο σχετικά με τις καταγγελίες. Εξάλλου, σύμφωνα με το “Facebook”, τα όποια ποσταρίσματα στη σελίδα, αναφορικά με την παράνομη είσοδο μεταναστών, απαγορεύτηκαν από τη δημοφιλή πλατφόρμα κοινωνικής δικτύωσης.

«Είμαστε ξεκάθαροι ότι όποιος βρεθεί να παρεμβαίνει ηθελημένα στην επιβολή του νόμου θα νιώσει την πλήρη ισχύ του νόμου. Οι εταιρείες μέσων κοινωνικής δικτύωσης έχουν την ευθύνη να προλαμβάνουν την παράνομη δραστηριότητα στις πλατφόρμες τους. Η διαδικτυακή μας υπηρεσία προτείνει την υποχρέωση των εταιρειών να εμποδίζουν τυχόν παράνομες δραστηριότητες στις εφαρμογές τους, συμπεριλαμβανομένου και του οργανωμένου μεταναστευτικού εγκλήματος», ανέφερε το βρετανικό υπουργείο Εσωτερικών σε σχόλιό του για την υπόθεση.

Σύμφωνα με τον εκπρόσωπο, οι βρετανικές αρχές έχουν ήδη αναπτύξει 6 αξιωματικούς στην Αλβανία. «Συνεργαζόμαστε στενά με τις αλβανικές αρχές και άλλους στην περιοχή, προκειμένου να πολεμήσουμε τις κύριες απειλές για το Ηνωμένο Βασίλειο», πρόσθεσε.

ΠΗΓΗ: SPUTNIK

5.

WALL STREET JOURNAL REPORTS BAHRAIN TARGETED BY IRANIAN CYBER ATTACKS

“Two former U.S. officials familiar with the matter confirmed the cyber breaches in Bahrain, saying that at least three entities had suffered intrusions,” The newspaper reported.

![Iranian flag and cyber code [Illustrative] Photo By: PIXABAY Iranian flag and cyber code [Illustrative]](https://images.jpost.com/image/upload/f_auto,fl_lossy/t_Article2016_ControlFaceDetect/433124)

WSJ reported that “suspected Iranian cyber offensives” and intrusions “rose above the normal level of Iranian cyber activity in the region,” and iare causing concern “that Tehran is stepping up its cyber attacks amid growing tensions.”

“On Monday, hackers broke into the systems of Bahrain’s National Security Agency – the country’s main criminal investigative authority – as well as the Ministry of Interior and the first deputy prime minister’s office, according to one of the people familiar with the matter,” the report said.

Although there is no proof that the attack was carried out by Tehran, United States intelligence officials have named the Iranian government as the suspected culprit. Bahrain, however, has not definitively claimed that the attack was executed by the Islamic republic.

The island nation, however, has accused Iran in the past “of conspiring with Qatar to subvert national unity and spark chaos in the region” after Iran and Qatar held a strategic maritime meeting in Tehran.

With regards to the alleged cyber attack, there has been no determination as to the extent of the damages or losses that Bahrain’s infrastructure has suffered.

Iranian government officials did not immediately respond for a request to comment on the charges, however Iran has “consistently maintained it is not hacking its neighbors.

The US has used cyber to gain intelligence and prevent escalations in the region, using unorthodox military tactics and tools to achieve these goals.

“In June, the U.S. military’s Cyber Command, in coordination with Central Command in the Middle East, launched cyber attacks against an Iranian intelligence group’s computer systems to control missile and rocket launches,” The Wall Street Journal reported in a previous article.

Bahrain is a strategic landing point for United States interests in the Middle East and it is the ongoing home to the US Navy’s Fifth Fleet and Central Command.

The accusation against the Iranian government not only sent a message to the Bahraini government, it also confuses the situation in the Gulf region even further, sending warning signs to the US, Israel and Saudi Arabia that there is now a very real possibility that state-sponsored cyber attacks will become a reality of both political and military warfare. The Bahrain intrusion indicates a further escalation and aggression in the Gulf region, whomever the culprits may be.

Identifying the origins of cyber attacks is difficult, considering that there is no physical evidence, but mainly just reports.

“Regional leaders in the Gulf – and security officials in the U.S. – believe Iran has been increasing its malicious cyber activity since tensions ratcheted up over a series of incidents across the Middle East [as well as] saber-rattling by the U.S. and Iran over Iran’s nuclear program and U.S. sanctions, people familiar with their discussions said,” The WSJ reported.

“On July 25, Bahrain authorities identified intrusions into its Electricity and Water Authority. The hackers shut down several systems in what the authorities believed was a test run of Iran’s capability to disrupt the country,” the WSJ report quoted a source familiar with the intrusion.

“They had command and control of some of the systems,” the source said.

However, with the information shared by the United States, the Bahrain Ministry of Interior released a statement assuring that it has “robust safeguards in place to protect Bahrain’s interests and essential public services from increasingly sophisticated external cyber attacks.”

Two former U.S. officials familiar with the matter confirmed the cyber breaches in Bahrain, saying that at least three entities had suffered intrusions.

“One of the officials said the breaches appeared broadly similar to two hacks in 2012 that knocked Qatar’s natural-gas firm RasGas offline and wiped data from computer hard drives belonging to Saudi Arabia’s Aramco national oil company, a devastating attack that relied on a powerful virus known as Shamoon,” the WSJ reported.

In addition to its existing protocol, the Bahraini government added that “in the first half of 2019, the authorities had successfully intercepted over 6 million attacks and over 830,000 malicious emails. The attempted attacks did not result in downtime or the disruption of government services.”

Many governments in the region, such as Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, have been spending millions of dollars to secure their cyber defenses against these kinds of attacks.

“This is the new normal and such attacks are likely to continue,” Norman Roule, the former intelligence manager for Iran at the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence told the WSJ. “For the last several years, Iran has undertaken, in waves, a series of attacks on Gulf state infrastructure.”

According to the report, three US-based cybersecurity firms have seen “signs” that the Islamic republic has focused cyber attacks on American interests, spear phishing emails and focusing their efforts on the American energy sector, such as oil and gas, as well as the US government itself.

The US Department of Homeland Security has already issued a warning that these attacks are a real possibility if tensions rise further between the two nations.

“This is an actor that has previously demonstrated a willingness to go destructive,” former DHS official Chris Krebs has said. “They’ve done it regionally. If their calculus changes, they could go global here.”

“Iran uses targets in the Middle East to sort of test capabilities before bringing them here,” a former senior U.S. intelligence official told the WSJ. “They’ve got some pretty good teachers. The Russians help them.”

Στις ΗΠΑ ο Πρωθυπουργός – Αν. Μεσόγειος και επενδύσεις τα θέματα συζήτησης με τον Τραμπ

Ο κ. Μητσοτάκης θα πραγματοποιήσει συνάντηση με τον πρόεδρο των ΗΠΑ, Ντόναλντ Τραμπ, καθώς και με στελέχη της αμερικανικής Κυβέρνησης.

Τα θέματα, που περιλαμβάνονται στην ατζέντα των ελληνοαμερικανικών συναντήσεων, θα είναι μεταξύ άλλων η διεύρυνση της στρατηγικής σχέσης Ελλάδας – ΗΠΑ, η προσέλκυση μεγάλων αμερικανικών επενδύσεων στην Ελλάδα και οι εξελίξεις στην Ανατολική Μεσόγειο μετά τις πρόσφατες τουρκικές κινήσεις.

Υπενθυμίζεται ότι ο πρωθυπουργός θα επισκεφθεί το Βερολίνο στις 29 Αυγούστου, ύστερα από πρόσκληση της Άνγκελα Μέρκελ.

7.

ΛΕΣ ΚΑΙ ΔΕΝ ΤΟ ΞΕΡΑΜΕ ΟΤΙ ΤΑ “ΕΠΙΑΣΑΝ” (ΚΑΙ) ΑΠΟ ΤΟΝ ΣΟΡΟΣ! (Η ΑΛΛΗ ΜΕΓΑΛΗ ΠΡΟΣΟΔΟΣ ΛΕΓΕΤΑΙ… “ΜΑΔΟΥΡΟ”)! ΟΜΩΣ, ΡΩΤΑΜΕ:

ΚΑΝΕΝΑΣ ΕΙΣΑΓΓΕΛΕΑΣ ΘΑ ΕΠΕΜΒΕΙ ΤΩΡΑ, ΟΠΩΣ ΕΠΙΒΑΛΛΕΤΑΙ, Η(ΔΙΑΖ) ΟΧΙ ΚΑΙ ΠΑΛΙ;

ΟΙ ΜΗΝΥΣΕΙΣ ΚΑΙ ΟΙ ΑΓΩΓΕΣ, ΕΝΘΕΝ – ΚΑΚΕΙΘΕΝ, ΚΟΤΖΙΑ – Π. ΚΑΜΜΕΝΟΥ, ΘΑ ΤΥΧΟΥΝ ΕΠΙΤΕΛΟΥΣ ΔΙΚΑΣΤΙΚΟΥ… ΑΚΡΟΑΤΗΡΙΟΥ Κε ΜΗΤΣΟΤΑΚΗ;

ΜΗΠΩΣ ΣΚΕΠΤΕΣΑΙ ΝΑ ΚΑΘΕΣΑΙ ΣΤΗΝ ΒΟΥΛΗ ΚΑΙ ΝΑ ΑΚΟΥΣ ΜΟΝΟΝ ΤΟΝ ΤΣΙΠΡΑ “ΝΑ ΣΟΥ ΚΑΝΕΙ ΠΛΑΚΑ” (ΝΑ ΝΟΜΙΖΕΙ ΤΟΥΛΑΧΙΣΤΟΝ), ΛΕΓΟΝΤΑΣ ΣΟΥ ΟΤΙ ΕΦΑΡΜΟΖΕΙΣ ΤΙΣ “ΠΡΕΣΠΕΣ”, ΤΙΣ ΟΠΟΙΕΣ ΞΕΡΕΙ ΠΟΛΥ ΚΑΛΑ ΟΤΙ ΕΤΣΙ ΠΟΥ ΤΗΝ “ΕΔΕΣΑΝ ΤΗΝ ΣΥΜΦΩΝΙΑ”, ΜΟΝΟΝ ΜΕ ΠΟΛΕΜΟ ΜΠΟΡΕΙ ΝΑ ΑΛΛΑΞΕΙ;

Ο 1ος ΠΟΥ ΤΟ ΤΟΝΙΣΕ ΑΥΤΟ, ΜΕΣΑ ΣΤΗΝ ΒΟΥΛΗ, ΗΤΑΝ Ο ΤΖΑΝΑΚΟΠΟΥΛΟΣ, (Ο ΣΗΜΕΡΙΝΟΣ ΚΟΙΝ. ΕΚΠΡΟΣΩΠΟΣ ΤΟΥ ΣΥΡΙΖΑ), ΠΟΥ ΕΙΧΕ ΜΙΛΗΣΕΙ, ΛΙΓΟ ΜΕΤΑ ΑΠΟ ΤΗΝ ΥΠΟΓΡΑΦΗ ΤΗΣ, ΚΑΙ ΕΙΧΕ ΠΕΙ: “ΕΥΤΥΧΩΣ ΠΟΥ ΕΙΝΑΙ ΕΤΣΙ Η ΣΥΜΦΩΝΙΑ ΠΟΥ ΔΕΝ ΑΛΛΑΖΕΙ ΜΕ ΤΙΠΟΤΑ“!

ΤΟΣΟ ΒΡΩΜΙΑΡΗΔΕΣ ΕΙΝΑΙ ΤΑ “ΔΙΕΘΝΙΣΤΟ-ΚΟΜΜΟΥΝΙΑ” ΤΟΥ ΣΥΡΙΖΑ, ΠΟΥ ΣΕ ΚΑΤΗΓΟΡΟΥΝ ΣΧΕΤΙΚΑ, ΚΛΠ, ΕΝΩ ΞΕΡΟΥΝ ΤΗΝ… ΠΟΥΣΤΙΑ ΤΟΥΣ!.. ΑΥΤΟΥΣ ΕΧΕΙΣ ΩΣ ΑΝΤΙΠΑΛΟΥΣ, ΤΟΥΣ ΝΕΟ-ΠΡΟΟΔΕΥΤΙΚΟΥΣ ΣΤΑΛΙΝΙΣΚΟΥΣ, ΠΟΥ ΘΕΛΟΥΝ ΚΙΟΛΑΣ ΝΑ ΕΚΦΡΑΣΟΥΝ ΚΑΙ ΤΟΝ… ΠΡΟΟΔΕΥΤΙΚΟ ΧΩΡΟ!.. ΝΑ ‘ ΧΑΜΕ ΝΑ ΛΕΓΑΜΕ!..

8.

CHINA’S SPIES IN U.S. UNIVERSITIES

Who will take notice?

In May of this year, in a commentary titled “United States, don’t underestimate China’s ability to strike back,” Wu Yuehe, a journalist at the People’s Daily, had this to say:

We advise the U.S. side not to underestimate the Chinese side’s ability to safeguard its development rights and interests. Don’t say we didn’t warn you!

A few weeks later, two Chinese professors at Emory university lost their jobs. Li Xiaojiang and Li Shishua, who were conducting research in the field of genetics, failed to disclose grants they received from nebulous institutions in China.

Two questions:

[1] Why were two scientists employed by an American university receiving grants from China?

[2] Why were the pair so reluctant to disclose the grants?

The answers to both questions are as simple as they are worrying. FBI Director Christopher Wray recently told senators that China is engaging in a concerted effort to steal its way to economic dominance. As I write, there are more than 1,000 investigations underway on intellectual property theft. Every single one of these investigations leads back to China.

The Chinese have been engaged in this sort of nefarious activity for years, and American institutes of education appear to be their prime focus. In August 2015, an electrical engineering student based in Chicago sent an email to a Chinese national titled “Midterm test questions.” Two years later, the email was the subject of an FBI probein the Southern District of Ohio. Law enforcement agents suspected the student was actually a plant, an intelligence officer who was sent to the United States for one reason only: to acquire technical information and share it with defense contractors in China.

Though investigators took note, they took no action. In 2018, however, Ji Chaoqun, the email’s author, was arrested in Chicago for allegedly acting within the United States as an illegal agent of the People’s Republic of China.

This arrest was long overdue. In 2013, Ji arrived in the United States on an F1 Visa, for the purpose of studying electrical engineering at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago. In 2016, according to a Department of Justice report: “Ji enlisted in the U.S. Army Reserves as an E4 Specialist under the Military Accessions Vital to the National Interest (MAVNI) program, which authorizes the U.S. Armed Forces to recruit certain legal aliens whose skills are considered vital to the national interest.”

Interestingly, as the report documents, in his application to participate in the MAVNI program, Ji specifically denied having had contact with a foreign government within the past seven years, which we now know was a blatant lie.

China gathers valuable research from U.S. universities by using nonconventional collectors, including professors, scientists, and students. According to a recent piece by Spectator’s Cole Carnick, the National Institutes of Health, a government agency that funds public health research at US universities,

found the Chinese government has developed systematic programs to unduly influence and capitalize on US-conducted research, with Chinese scholars divulging exclusive research to Chinese intelligence.

In March, according to a Wall Street Journal report, Chinese hackers targeted research on maritime technology at several universities, including the University of Hawaii, the University of Washington, Penn State, and even MIT.

Understandably, FBI officials have advised universities across the land to review ongoing research involving Chinese individuals that could have militaristic applications.

Aside from infiltrating scientific research, the Chinese party actively attempts to influence campus discussions about China through student organizations. As a 2018 Hoover institution report noted, the Chinese Students and Scholars Association (CSSA), the official organization for overseas Chinese students and scholars registered in most colleges, universities, and institutions outside of China. takes directives from the Chinese government and develops close ties with China’s consulates. Worryingly, as the report notes, when campus events focus on Tibet, Taiwan, Hong Kong, or the Uighurs, CSSA representatives contact officials in China, who then ask (or demand) the given university to silence any distasteful discussions.

Two years ago, the University of California San Diego extended an invitation to the Dalai Lama. Unsurprisingly, the university quickly received requests from the campus CSSA and China’s consulate in Los Angeles to rescindthe invitation. Thankfully, the university refused to acquiesce. Chinese officials, clearly unimpressed, prohibited future scholarship funds for Chinese students studying at UCSD.

As Jeanine Frost once wrote,

There is only one way to fight, and that’s dirty. Clean gentlemanly fighting will get you nowhere but dead, and fast. Take every cheap shot, every low blow, absolutely kick people when they’re down, and maybe you’ll be the one who walks away.

Chinese officials, clearly fans of Frost’s work, are prepared to fight dirty. They are prepared to lie, steal and cheat.

China, not Russia, is the existential threat to the United States.

America’s failure to realize this fact could prove catastrophic.

9.

REMEMBERING THE FIRST AND FORGOTTEN ARMENIAN GENOCIDE OF 1019

Its more popular modern counterpart is the tip of the iceberg.

Raymond Ibrahim is a Shillman Fellow at the David Horowitz Freedom Center.

Last April 24 was Armenian Genocide Remembrance Day. Millions of Armenians around the world recollected how the Islamic Ottoman Empire killed—often cruelly and out of religious hatred—some 1.5 million of their ancestors during World War I.

Ironically, most people, including most Armenians, are unaware that the first genocide of Christian Armenians at the hands of Muslim Turks did not occur in the twentieth century; it began in 1019—exactly one-thousand years ago this year—when Turks first began to pour into and transform a then much larger Armenia into what it is today, the eastern portion of modern day Turkey.

Thus, in 1019, “the first appearance of the bloodthirsty beasts … the savage nation of infidels called Turks entered Armenia … and mercilessly slaughtered the Christian faithful with the sword,” writes Matthew of Edessa (d.1144), a chief source for this period. Three decades later the raids were virtually nonstop. In 1049, the founder of the Turkic Seljuk Empire himself, Sultan Tughril Bey (r. 1037–1063), reached the unwalled city of Arzden, west of Lake Van, and “put the whole town to the sword, causing severe slaughter, as many as one hundred and fifty thousand persons.”

After thoroughly plundering the city—which reportedly contained eight hundred churches—he ordered it set ablaze and turned into a desert. Arzden was “filled with bodies” and none “could count the number of those who perished in the flames.” The invaders “burned priests whom they seized in the churches and massacred those whom they found outside. They put great chunks of pork in the hands of the undead to insult us”—Muslims deem the pig unclean—“and made them objects of mockery to all who saw them.”

Eight hundred oxen and forty camels were required to cart out the vast plunder, mostly taken from Arzden’s churches. “How to relate here, with a voice stifled by tears, the death of nobles and clergy whose bodies, left without graves, became the prey of carrion beasts, the exodus of women … led with their children into Persian slavery and condemned to an eternal servitude! That was the beginning of the misfortunes of Armenia,” laments Matthew, “So, lend an ear to this melancholy recital.”

Other contemporaries confirm the devastation visited upon Arzden. “Like famished dogs,” writes Aristakes (d.1080) an eye witness, “bands of infidels hurled themselves on our city, surrounded it and pushed inside, massacring the men and mowing everything down like reapers in the fields, making the city a desert. Without mercy, they incinerated those who had hidden themselves in houses and churches.

Similarly, during the Turkic siege of Sebastia (modern-day Sivas) in 1060, six hundred churches were destroyed and “many [more] maidens, brides, and distinguished ladies were led into captivity to Persia.” Another raid on Armenian territory saw “many and innumerable people who were burned [to death].” The atrocities are too many for Matthew to recount, and he frequently ends in resignation:

Who is able to relate the happenings and ruinous events which befell the Armenians, for everything was covered with blood. . . . Because of the great number of corpses, the land stank, and all of Persia was filled with innumerable captives; thus this whole nation of beasts became drunk with blood. All human beings of Christian faith were in tears and in sorrowful affliction, because God our creator had turned away His benevolent face from us.

Nor was there much doubt concerning what fueled the Turks’ animus: “This nation of infidels comes against us because of our Christian faith and they are intent on destroying the ordinances of the worshippers of the cross and on exterminating the Christian faithful,” one David, head of an Armenian region, explained to his countrymen. Therefore, “it is fitting and right for all the faithful to go forth with their swords and to die for the Christian faith.” Many were of the same mind; records tell of monks and priests, fathers, wives, and children, all shabbily armed but zealous to protect their way of life, coming out to face the invaders—to little avail.

Anecdotes of faith-driven courage also permeate the chronicles. During the first Turkic siege of Manzikert in 1054, when a massive catapult pummeled and caused its walls to quake, a Catholic Frank holed up in with the Orthodox Armenians volunteered to sacrifice himself: “I will go forth and burn down that catapult, and today my blood shall be shed for all the Christians, for I have neither wife nor children to weep over me.” The Frank succeeded and returned to gratitude and honors. Adding insult to injury, the defenders catapulted a pig into the Muslim camp while shouting, “O sultan [Tughril], take that pig for your wife, and we will give you Manzikert as a dowry!” “Filled with anger, Tughril had all Christian prisoners in his camp ritually decapitated.”

Between 1064 and 1065, Tughril’s successor, Sultan Muhammad bin Dawud Chaghri—known to posterity as Alp Arslan, a Turkish honorific meaning “Heroic Lion”—“going forth full of rage and with a formidable army,” laid siege to Ani, the fortified capital of Armenia, then a great and populous city. The thunderous bombardment of Muhammad’s siege engines caused the entire city to quake, and Matthew describes countless terror-stricken families huddled together and weeping.

Once inside, the Islamic Turks—reportedly armed with two knives in each hand and another between their teeth—“began to mercilessly slaughter the inhabitants of the entire city . . . and piling up their bodies one on top of the other. . . . Beautiful and respectable ladies of high birth were led into captivity into Persia. Innumerable and countless boys with bright faces and pretty girls were carried off together with their mothers.”

The most savage treatment was always reserved for those visibly proclaiming their Christianity: clergy and monks “were burned to death, while others were flayed alive from head to toe.” Every monastery and church—before this, Ani was known as “the City of 1001 Churches”—was pillaged, desecrated, and set aflame. A zealous jihadi climbed atop the city’s main cathedral “and pulled down the very heavy cross which was on the dome, throwing it to the ground,” before entering and defiling the church. Made of pure silver and the “size of a man”—and now symbolic of Islam’s might over Christianity—the broken crucifix was sent as a trophy to adorn a mosque in modern-day Azerbaijan.

Not only do several Christian sources document the sack of Armenia’s capital—one contemporary succinctly notes that Muhammad “rendered Ani a desert by massacres and fire”—but so do Muslim sources, often in apocalyptic terms: “I wanted to enter the city and see it with my own eyes,” one Arab explained. “I tried to find a street without having to walk over the corpses. But that was impossible.”

Such is an idea of what Muslim Turks did to Christian Armenians—not during the Armenian Genocide of a century ago but exactly one thousand years ago, starting in 1019, when the Turkic invasion and subsequent colonization of Armenia began.

Even so, and as an example of surreal denial, Turkey’s foreign minister, capturing popular Turkish sentiment, recently announced that “We [Turks] are proud of our history because our history has never had any genocides. And no colonialism exists in our history.”

Note: The above account is excerpted from Ibrahim’s Sword and Scimitar: Fourteen Centuries of War between Islam and the West — a book that CAIR did everything it could to prevent the U.S. Army War College from learning about.

10.

ISRAEL’S SUCCESSFUL TESTING OF ARROW 3

Not only a great technological breakthrough, but a critical component in Israel’s defense.

The Start-Up nation that has become a technological powerhouse has once again displayed its inventive capacity to provide protection for the people of Israel. Earlier last month, in Alaska’s air space, Israel successfully tested the Arrow 3 interceptor, its latest anti-ballistic missile-missile. The testing of the Arrow 3 system in Alaska proved that it is able to intercept and destroy an incoming ballistic missile with a nuclear warhead in the outer atmosphere before it dangerously splits and flies toward its target. The test, conducted at the Spaceport Complex Alaska in Kodiak, was a joint effort between the Israel Missile Defense organization of the Directorate of Defense Research and Development, and the U.S. Missile Defense Agency. Israel’s Aerospace Industries and Boeing jointly developed the Arrow. The Arrow system became operational in 2017 and has been deployed to counter Iranian and Syrian missiles.

The Arrow 3 interceptor successfully demonstrated its capability against the exo-atmospheric target. Vice Admiral Jon Hill, the director of the Missile Defense Agency said, “These successful tests mark a major milestone in the development of the Arrow weapon system.” He added, “it provides confidence in the future capabilities to defeat the developing threats in the region.” As for the State of Israel, the successful testing of the Arrow 3 interceptor is particularly encouraging for Israeli civilians. They now know that Arrow 3 provides the Jewish state with a security net against an Iranian attack with ballistic missiles carrying nuclear warheads. Then again, it is essential for Israel to produce an appreciable quantity of the Arrow 3 launcher and interceptor missiles to forestall an Iranian or possibly a Hezbollah attack with multiple missiles launched at once.

At the July 28, 2019 cabinet meeting, Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said, “Our innovative tests in Alaska took part in collaboration with our ally, the United States. The tests outside the atmosphere went perfectly: each target was a bulls-eye! Israel has the ability to send ballistic missiles to Iran, a huge gain for Israel’s security.” The successful Israeli testing of the Arrow 3 exposes Iran’s vulnerability to an Israeli missile attack. Iran lacks the weapon system that is capable of intercepting incoming ballistic missiles. It is now noteworthy to recall PM Netanyahu’s warning to Iran that Israel would destroy Iran’s nuclear facilities should Tehran become an imminent nuclear threat to Israel. The inclusion of the Arrow 3 in Israel’s arsenal makes Netanyahu’s warning much more credible. Israel, however, is unlikely to initiate a war with Iran unless the Islamic Republic is close to producing a nuclear bomb or invades Israeli territory.

Another reason why the Arrow 3 is critical to Israel’s security is that when it hits an enemy missile with a nuclear payload, the explosion and the radioactive material it spreads will remain in space rather than contaminate Israeli soil or its neighbors.

Iran is seeking to develop ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads that can split when they re-enter the atmosphere. Insofar as western and Israeli intelligence services would reveal, Iran does not yet have the capabilities to produce a small enough nuclear warhead that can fit into a Shihab 3 ballistic missile the Iranians have or similar missiles that might be able to reach Israel. Iran might also be working on another viable option, namely, a cruise-missile that can carry a nuclear warhead. Using aircrafts or ships that would carry a nuclear devise would be too risky for the Iranians since it could be intercepted and destroyed before they reached their destination.

Israel’s technological contributions to the world have been immense considering its lack of natural resources and its smallness. In facing its Arab and now Iranian enemies, with far greater manpower and natural resources (or arms in the early years in particular), Israelis resolved to survive with the famous Hebrew expression of ‘Ein Breira’ (there is no choice, we must use our brains to overcome or perish). With the Holocaust always in the background and motivated by the need to defend itself against its hostile neighbors, even in the earliest days of the State, companies such as Israel Aviation industries (IAI), Rafael, Elbit, and Tadiran, produced advanced technologies for the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), eventually growing into an international export industry.

In the 1970’s, Israel’s technological know-how began to be applied far beyond the military and spread into the civilian market. Simultaneously, international corporate giants established research and development centers in Israel, including such companies as Motorola, IBM, National Semiconductors, and especially Intel. Israeli ingenuity contributed in a significant way to Intel’s world dominance, which is based on its continuing ability to innovate. The world’s largest chip maker relies on Israeli talent for many of its breakthroughs created in Intel’s R&D centers in Haifa and Petach Tikvah, where the Pentium M chip was created. Pentium M lies at the heart of the Centrino-, which enables Wi-Fi to operate. World renowned companies such as Cisco and Microsoft rely heavily on Israeli R&D facilities. Most of the Window NT operating system was developed by Microsoft-Israel.

Israeli technological innovations are not limited to the computer, they go into homes and improve personal lives. More importantly, Israeli technology saves lives. One such example is the PillCam, the first ever ingestible video camera, which helps doctors diagnose gastrointestinal diseases likes Crohn’s and Celiac. There are too many lifesaving devises and cures to include in one article.

Israel’s lifesaving Military related technology includes the Emergency Bandage (Israeli bandage), Visual-ICE, which provides a minimally invasive, easy to use system to precisely destroy solid cancer tumors of the kidney, lung, bone, liver, and prostate, and they enable nerve ablation for pain management. Visual-ICE, developed by Galil Medical, took its innovative cryotherapy, based on the cooling technologies taken from the tip of the Rafael missiles. Cardiac Catheterization was developed by biosense Webster, which is an Israeli company. It is a computer-vision tracking mechanism originally developed for the Israeli air force (IAF) by Elbit, leading to the miniaturized 3D cardiac mapping and navigation technology built inside the revolutionary Catheters. The IDF has served as an incubator for the Start-Ups that have sprung out of it.

The Arrow 3 Interceptor is not only a great technological breakthrough, it is an essential component that serves to complete Israel’s defense against an attack by enemy missiles. It is part of a multi-layered defense shield, providing a third layer of defense. Arrow 3 is designed to intercept long-range missiles that could strike Israel from thousands of miles away. The David’s Sling system provides protection from medium to long-range missiles or suicide drones. Finally, the more familiar Iron Dome is the third layer of defense. It has been used effectively to intercept short and medium range rockets, the kind Hamas has fired in recent years, targeting Israeli population centers.

Yaakov Katz, co-author of The Weapon Wizards: How Israel Became a High-Tech Military Superpower, wrote, “Israel is the only country in the world that has used missile defense systems in times of war. These systems do more than just save lives. They also give the country’s leadership ‘diplomatic maneuverability,’ the opportunity to think and strategize before retaliating against rocket attacks.”

* * *

Photo by U.S. Missile Defense Agency

11.

HOW IRAN IS TAKING OVER SYRIA

And what Trump needs to do about it.

A recent survey put out by Fox News found that six in ten Americans believe that Iran poses a threat to America’s safety. These Americans are backed up in their convictions as they recently witnessed the Iranian Revolutionary Guards threatening a British warship. This came after Iran attacked a Japanese tanker, had its proxies attack an international airport in Saudi Arabia and seized a British ship. As tensions flare in the region, it is of critical importance to recall that Iran does not merely pose a threat to the US in the Persian Gulf. The Mullahs can also harm America via their proxies in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon and Yemen. Given this fact, it is of utmost importance that Americans pay attention to how the Islamic Republic is entrenching itself in Syria.

A recent report issued by the Safadi Center found that:

there has been increased infiltration by Iran-supported militias along the border with Israel. Four Lebanese Hezbollah bases were established in Southern Syria over the past year, three of them in Zara and one of them in Quneitra.

The report claims that Hezbollah utilizes these bases in order to train new volunteers and to store weapons and armaments for the terror group. According to the Safadi Center, Hezbollah and the Iranian regime are increasingly spreading out along the Golan Heights, thus posing a strategic threat to the State of Israel:

This is done in order to realize the regional ambitions of the Iranian regime, which seeks to establish a Shia Crescent from Tehran to the Mediterranean Sea.

“Hezbollah is not satisfied with providing training bases for the regime and its volunteers,” Mendi Safadi, the head of the Safadi Center for International Diplomacy, Research, Public Relations and Human Rights, states. He continues:

They also established militant groups and security cells in Daraa and Quneitra in order to obtain wide deployment in the region via families that support recruiting children. This is done so that they can obtain comprehensive military control over the border in the Hermon region till Swaida via the Golan Heights and the Jordanian border. Hezbollah has recruited in recent months hundreds of residents of the Quneitra region. In addition, other secret groups have done special training on rockets in the military academy in Aleppo and Lebanon, where participants received from Hezbollah a monthly salary of 120,000 Syrian liras in addition to military uniforms for combat missions so that they can fight alongside the Syrian military.

The report issued by the Safadi Center has been confirmed by Syrian Kurdish dissident Sherkoh Abbas, who affirms that Iran and Hezbollah not only are more and more entrenched along the border with Israel but are increasingly taking over all of Syria. He states,

Iran is in charge of Syria. Assad is a figurehead for Syria but the people who run the day to day operations in Syria are Iran. They have bases throughout the country. We see their influence in all of Syria in general. In fact, they have been working on changing the character of Syria so that it will be Shia and the demographics are changing in favor of groups allied with Iran. They are shipping in oil tankers, weapons and people. It is a fact.

“It is beyond the Israel border,” Abbas adds, stressing that:

Iran started not just now. They supported groups and are building up their influence slowly in Syria, economic to military. Now, they fully control Syrian day to day life. It is not so easy to detect anymore. They gave citizenship to people, changed neighborhoods and they let people economically rely on them. People began to rely on them. It is not easy to detect like an army. They look Syrian. They dress like Syrians. They learned to speak Syrian Arabic. They embedded themselves in Syrian society. What Iran is doing is more a threat to Syria and the whole Middle East for they are embedded in Syria.

Abbas proclaims that eventually all of the ethnic and religious cleansing that is occurring in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon and Yemen will be a nightmare for the world to manage for a number of reasons:

This is firstly because of the refugee displacement and also the changing the landscape of the Middle East. Where are you going to strike? They are embedded in schools and hospitals. It is important for the US and Israel to realize that they need to address the Syrian issue. Any political solution is in favor of Iran. The Iranians view Syria as a way to bypass sanctions and use its ports, airports and seaports and energy sources to make it a market or to bring it from there to Iran. This is the only way to bypass the international community. Unfortunately, the US, Israelis and Europeans have not recognized it. They can put sanctions on Iran but Syria, Lebanon, Yemen and Iraq serve its needs.

Abbas also notes that as Iran extends its sphere of influence, it puts pressure on groups that are traditionally friendly to the US, such as the Christians, Kurds, Yezidis, etc. He also declares that this creates more disgruntled Sunnis, which can lead to the reemergence of ISIS or something worse:

They will make ISIS look moderate. The sooner the US and Europeans address the issue and recognize Syria as a failed state and try to have Iran’s influence reduced as well as Russia’s, there will be a better Middle East for them with less radical Islam and a smaller refugee crisis. It will allow certain sectors of Syria to prosper. That has the potential to make the Middle East safer versus burying ones head in the sand. Now is the time to recognize these failed states as such and to support your true allies in these areas and to make sure other people don’t go the same way as Assad by finding a way to let them rebuild. That is something that needs to be addressed.

Given that this is the reality, US President Donald Trump should not just apply more sanctions on Iran. He also needs to address how Iran is taking over Syria, Iraq, Lebanon and Yemen, where it is establishing a Shia Crescent. He needs to tackle how Turkey is increasingly building an alliance with Iran. This reality makes it pivotal for the US to keep a presence in Syria, especially as Turkey threatens to engage in a military operation if it can’t come to an agreement with the US. Such a military operation combined with the Iranian threat in the rest of Syria would transform the entire Kurdish region into another Afrin, where ISIS is presently reemerging. The only way to avoid such a scenario is for the US to go after Iran’s proxies in the same manner that they go after the Iran regime itself – and to not abandon Syria to Iran.

Rachel Avraham is a political analyst working at the Safadi Center for International Diplomacy, Research, Public Relations and Human Rights. She is the author of “Women and Jihad: Debating Palestinian Female Suicide Bombings in the American, Israeli and Arab media.”

12.

NEW EVIDENCE UNVEILS DISTURBING FACTS ABOUT HILLARY’S EMAIL SCANDAL

FBI is implicated in destroying evidence to benefit Clinton.

In breaking news, the American Center for Law and Justice or ACLJ (Jay Sekulow’s organization, not related to his role as the President’s attorney), has obtained actual copies of the immunity agreements pertaining to Cheryl Mills and Heather Samuelson in the Hillary email scandal. This was a stunning litigation win, hard-fought after years of litigation by the ACLJ attorneys, who were unable to extract the documents through the normal FOIA processes, due to a lack of cooperation by the government.

In reviewing what the agreements uncovered, keep in mind that Cheryl Mills was Secretary Clinton’s Chief of Staff at the State Department and then bizarrely, she subsequently served as Clinton’s attorney, representing her in the email scandal. Heather Samuelson worked on Hillary Clinton’s 2008 campaign, and then became a Senior Advisor to her at the State Department, as well as the White House liaison. Somehow, she also became one of Clinton’s personal attorneys during the email scandal.

The immunity agreements issued by the government, were crafted so that the agencies could extract information from the parties, despite the fact that this is not necessary because DOJ has the power to require that the information be turned over. Clinton kept classified emails on a private server in violation of Federal law, and the immunity agreements reveal that both Cheryl Mills and Heather Samuelson were actively involved in the cover-up of these emails as well as in the destruction of evidence. According to Jordon Sekulow, Executive Director of the ACLJ, it is extremely unusual for someone involved in a criminal cover up, who needs an immunity deal to ensure the evasion of jail time, later becomes the attorney representing the other potential criminal or co-conspirator.

The agreements issued were with DOJ and the FBI. They asserted that Mills and Samuelson would turn over the computers to them, but stipulated that they weren’t turning over “custody and control”. This critical point is a legal and factual bunch of bunk. The FOIA statute applies to information in the agencies’ “custody and control”. Anything not in their custody or control cannot be FOIA’d. It is impossible to have an agency physically have a computer and not have it in their “custody or control.” Custody and control is not something that suspects have to expressly give over or agree to give over. When they give over the evidence, then obviously, as a matter of fact, they are also giving the agency “custody and control” over that evidence. Suspects cannot withhold “custody and control” by mere words or lack of consent, as consent is not required. In other words, these agreements are extremely flawed and whomever signed off on them should be investigated and perhaps prosecuted. It is clear that the purpose of this clause was to make the arguably illegal activities of Mills and Samuelson out of the reach of FOIA — in other words, it would be withheld from the public. This is the very definition of corruption.

Additionally, the immunity agreements were broad in scope. There were numerous charges that the agreements gave them immunity from including potential violations of the Federal Records Act, the Classified Information Act and the Espionage Act. According to the ACLJ, nobody has ever gotten immunity from the Espionage Act before. Normally, immunity is for lesser crimes like obstruction of justice, but not espionage. If Mills and Samuelson were charged and convicted of every crime from which they received immunity, they would be potentially subject to twenty-eight years in jail each.

After Clinton illegally sent classified emails on a private server and cell phones (and by the way, people have gone to jail for this even when they did so accidentally because it’s that serious), and after Mills and Samuelson purposely worked to cover up and conceal both the emails and the destruction of evidence, and after they were given a sweetheart deal that nobody in history has ever gotten, they became the attorneys for Clinton, representing her in the email case. This shouldn’t be allowed because it is a conflict of interests, and not only gives the appearance of impropriety, but indeed, constitutes actual impropriety.

Subsequently, Mills and Samuelson finally gave the computers over to the FBI, which per their agreements, limited the FBI’s investigation. The FBI agreed to limit a) the method by which the emails investigated would be obtained; b) the scope of files which would be investigated, and c) the timeframe parameters for investigated emails. In other words, the FBI agreed in the immunity contracts not to do a full investigation on the Clinton emails. To make matters worse, again, per the immunity agreements, the FBI agreed to destroy the computers that had the back-up emails. As Congressman Jim Jordan referenced during the Mueller hearings recently, the FBI used bleachBit to purge the server so the information could never be accessed in the future and used hammers to smash the cell phones involved. In other words, the FBI and DOJ participated in the destruction of the evidence. In effect, this constitutes is a conspiracy between the Obama DOJ (under Loretta Lynch) and the Comey-led FBI to cover up Clinton’s crimes.

Shortly thereafter, Comey came out publicly and held a press conference exonerating Clinton from any criminal activity, knowing full well that she was never thoroughly investigated, and that his own agency had participated in the destruction of evidence.

To reiterate Comey’s assertions, he stated that Clinton had been “extremely careless” in her handling of classified and sensitive information, but not “grossly negligent”, even though the definition of grossly negligent is extremely careless. Gross negligence is the language in the statute necessary to prosecute someone who does this and Comey inaccurately professed that no prosecutor would pursue a case based on these facts, even though those with lesser evidence have indeed been charged.

Currently, there are investigations taking place pertaining to the Clinton email scandal cover-up, as well as the origins of the Trump investigation by the Mueller team, including the roots of the FISA applications. All of the documents uncovered by the ACLJ’s legal win will constitute valuable evidence for AG Bill Barr, the IG and others. Many who follow what is really going on, on a day to day basis have been repeatedly disappointed in the biased and one-sided investigations and the cover-up or blatant disregard of critical facts implicating the pro-Clinton, anti-Trump teams. But Bill Barr and his team are fairly new to the process. He and others, including John Durham, will finally have the opportunity to get to the bottom of all this — and finally disclose the real collusion, corruption, and obstruction. There’s still hop

13.

IS A HAMAS – ALLIED HATE GROUPINFLUENCING THE 2020 DEM PRIMARIES?

The foreign election interference the Democrats don’t want to talk about.

Daniel Greenfield, a Shillman Journalism Fellow at the Freedom Center, is an investigative journalist and writer focusing on the radical Left and Islamic terrorism.

After disrupting a Holocaust Remembrance Day event at U.C. Berkeley, Hatem Bazian told supporters to look at all the Jewish names on the buildings, “take a look at the type of names on the building around campus — Haas, Zellerbach — and decide who controls this university.”

In 2017, Bazian, the founder of hate groups such as Students for Justice in Palestine and American Muslims for Palestine, retweeted anti-Semitic memes from a Holocaust denial Twitter account.

After the backlash, the Islamist hate group leader claimed that he had Jewish friends.

Next year, Bazian’s Jewish friends came out of the closet when he boasted through a megaphone outside Senator Kamala Harris’ office, while protesting in support of Hamas attacks on Israel, that, “AMP and IfNotNow are coming together.”

AMP was Bazian’s own hate group, whose board members had been accused of supporting Hamas. The organization has been sued by the parents of David Boim, an American teen murdered by Hamas.

IfNotNow is an anti-Israel hate group notorious for targeting Jewish charities and organizations. A member of the hate group had just recited a mock Kaddish, the Jewish prayer for the dead, for what the two hate groups falsely claimed was a massacre of civilian protesters in Gaza. In fact, Hamas had admitted that 50 of the 62 killed in the attacks on Israel were members of the terrorist organization.

Officially, If Not Now claims to be a Jewish protest movement against the “occupation”. In July, Max Berger, its radical co-founder, faced his own backlash over a tweet declaring that he, “would totally be friends with Hamas”. Berger had praised the violent Hamas riots and claimed that, “the biggest obstacle to peace in Israel-Palestine is the bigotry of American Jews.” The most politically prominent member of IfNotNow was New York State Senator Julia Salazar, the leader of a Christian campus organization, born into a Catholic family, who joined the anti-Israel hate group while falsely claiming to be Jewish.

Whether IfNotNow’s members are Jewish, there is no doubt that they make a point of targeting Jews. That’s what IfNotNow really has in common with Hatem Bazian and members of the AMP hate group.

Neveen Ayesh, the executive director of AMP-Missouri, had tweeted anti-Semitic hate such as, “#crimesworthyoftherope being a Jew”, ” “I hate Jews… I hate Israelis”, and “I just want to spit in their faces. All of them any Jew Israeli.”

As documented by Canary Mission, IfNotNow activist Hal Rose had been interviewed by Ayesh in an anti-Israel conference. Despite her collaboration with an anti-Semitic activist who had called for the murder of Jews, Rose has claimed that ICE’s attempts to detain illegal aliens are just like the Holocaust. She also defended Rep. Omar’s anti-Semitism by arguing that AIPAC’s actions “often fall into antisemitic stereotypes.”

In 2017, IfNotNow had invited Taher Herzallah of AMP to train its members on Islamophobia. Herzallah had posted that “Hamas rockets are an oppressed people’s cry for help” and celebrated photos of wounded Israeli soldiers as a “beautiful site”. He had even defended a California Imam’s call for killing Jews by contending that, “The Jewish community in America overwhelmingly supports Israel.”

Next year, also as documented by Canary Mission, Herzallah was back teaching IfNotNow activists about “Palestinian non-violent resistance and how our community can take action to oppose the Israeli Military’s recent actions.”

At an AMP conference a few years earlier, Herzallah had asked, “What if, as Muslims we wanted to establish an Islamic state? Is that wrong? What if, as Muslims, we wanted to use violent means to resist occupation? Is that wrong?”

The partnership between AMP and If Not Now applies Hatem Bazian’s campus politics to the political process. Like Students for Justice in Palestine, a campus hate group that uses its handful of Jewish members as political shields against accusations of anti-Semitism, IfNotNow’s presence whitewashes a violently genocidal cause. And IfNotNow can go where AMP, with its history of Hamas ties, can’t.

IfNotNow co-founder Max Berger works for Senator Elizabeth Warren. IfNotNow members have been able to pose with Warren and Senator Bernie Sanders, and win their support for their hateful cause. The hate group was also able to corral Biden, Buttigieg and Booker. Though with little to show for it. But despite an outcry from the Jewish community, the Warren campaign failed to dump Berger.

IfNotNow has hired six activists to operate in New Hampshire in order to influence the 2020 election. And that’s why Canary Mission’s campaign to bring attention to its alliance with AMP is so critical.

Canary Mission, a Jewish civil rights organization exposing anti-Semitic leftist hate groups online, has launched a campaign to call attention to IfNotNow’s ties with the Hamas supporters and anti-Semitic racists of American Muslims for Palestine. Its report names 25 AMP figures who have spread anti-Semitic hate and 58 IfNotNow members who have worked with AMP.

The issue is especially urgent since IfNotNow has made it clear that it is seeking to influence the 2020 Democrat primaries and its partner, AMP, has been accused of links to a foreign terrorist organization.

Three years ago, Jonathan Schanzer, a former terror finance analyst for the Treasury Department, and a senior vice president for research at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, testified in Congress that organizations funding Hamas had gravitated to American Muslims for Palestine.

The groups in question include the Islamic Association for Palestine, which had been set up by the Muslim Brotherhood.

Hamas is also an affiliate of the Muslim Brotherhood.

He noted that, “AMP is a not-for-profit corporation, but not a federal, 501c3, tax-exempt organization. Therefore, AMP does not have to file an IRS 990 form that would make its finances more transparent.”

That makes it hard to know where AMP’s funding is really coming from.

The Muslim Brotherhood is an international terrorist organization whose past members have included Osama bin Laden, along with other key Al Qaeda figures. Its political activists have a history of building networks in order to influence foreign governments and manipulate political elections.

IfNotNow is partnered with a group linked to hostile foreign political interests, and is attempting to influence the upcoming presidential election. And the same Democrats who are still warning about Russian election interference show no interest when they’re the ones being influenced.

Senator Elizabeth Warren has announced a new election security plan, but is still employing Max Berger. Warren’s failure to cut ties with Berger and his IfNotNow hate group raises questions of collusion.

In 2008, a report showing Gazans running a phone bank for Obama failed to lead to any action. If a Hamas ally is once again interfering in a presidential election, it must be meaningfully addressed.

There can be no place for supporters of a foreign terrorist group in the 2020 election.

14.

Trump Names Counterterrorism Chief as Acting Director of National Intelligence

U.S. President Donald Trump has wiped the slate clean at the nation’s lead intelligence agency.

Trump accepted the resignation Principal Deputy Director of National Intelligence Sue Gordon late Thursday, less than two weeks after announcing the agency’s director, Dan Coats, would also be leaving.

“Sue Gordon is a great professional with a long and distinguished career,” the president said on Twitter, adding he had “great respect for her.”

Less than an hour later, Trump tweeted Joseph Maguire, a retired admiral who has been serving as director of the U.S. National Counterterrorism Center, would take over as acting director of national intelligence Aug. 15, the day the resignations of Coats and Gordon are to take effect.

Trump had sparked speculation that Gordon, a 30-year veteran of the intelligence community, was on her way out when he tweeted he was planning to name an acting director following Coats’ resignation last month.

Chain of command

By U.S. law, in the absence of a director of national intelligence, the principal deputy director of national intelligence is supposed to become the acting director.

When asked earlier this month about his reluctance to allow Gordon to assume the role of acting director, Trump told reporters, “I like Sue Gordon.”

“She’s there now and certainly she’ll be considered for the acting,” he added. “That could happen.”

Unlike outgoing Director of National Intelligence Coats, who publicly clashed with Trump on several occasions, Gordon tended to avoid any public spats.

Asked about Trump during an appearance in Washington last October, Gordon said “he has a penchant for action,” describing him as “really interesting.”

But like Coats, Gordon held a firm line on the threat from Russia, especially when it came to the upcoming presidential election in 2020.

At a conference in Washington in June, Gordon called Moscow a “significant cyber influence threat.”

“Their real goal is no longer to acquire the information but to alter our decision-making,” she added, the comment coming just a day before Trump met with Russian President Vladimir Putin at the Group of 20 Summit in Osaka, Japan.

In her resignation letter, Gordon wrote it was an honor to serve as the principal deputy director of intelligence for the past two years.

“As you ask a new leadership team to take the helm, I will resign my position,” she wrote. “I am confident in what the Intelligence Community has accomplished and what it is poised to do going forward.”

But in a note with the letter, Gordon made clear she was not leaving of her own accord.

“I offer this letter as an act of respect & patriotism, not preference,” she told Trump. “You should have your team.”

Reaction from Intelligence Community

Former U.S. intelligence officials were quick to react to Gordon’s resignation on social media.

“Sue Gordon’s forced resignation as deputy DNI today is an assault on intelligence,” Larry Pfeiffer, a former CIA chief of staff and former senior director of the White House Situation Room, tweeted.

Rolf Mowatt-Larssen, a former veteran CIA officer who served as the spy agency’s Europe division chief, was even more pessimistic.

“This is a sign Trump is going to do something unacceptable in his efforts to control intelligence & law enforcement and consolidate power,” he tweeted.

Some key lawmakers also expressed a mix of appreciation for Gordon’s career and distress and what they perceived as her ouster.

“This is a real loss to our intelligence community,” Senate Intelligence Committee Vice Chair Mark Warner, a Democrat, said in a statement late Thursday. “Once again the president has shown that he has no problem prioritizing his political ego even if it comes at the expense of our national security.”

The committee’s chairman, Republican Senator Richard Burr, likewise lamented Gordon’s departure, calling it “a significant loss.”

“I will miss her candor and deep knowledge of the issues,” Burr said in a statement.

But Burr also praised National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC) Director Maguire, the president’s choice to lead the intelligence community in the interim.

“I’ve known Admiral Maguire for some time and I have confidence in his ability to step into this critical role,” Burr said.

Career in the Navy

Maguire, who retired from the U.S. Navy in 2010 after a 36-year career as a naval special warfare officer, has led the NCTC since December 2018.

During his confirmation hearing before the Senate Intelligence Committee, Maguire assured lawmakers he would not allow politics to influence how intelligence would be presented to the president.

“I am more than willing to speak truth to power,” he said told lawmaker at the hearing last year.

Coats also expressed confidence in Maguire to lead the U.S. Intelligence Community on an interim basis.

“I am pleased that the President has announced that Joe will serve as Acting DNI,” Coats said in a statement late Thursday. “Joe has had a long, distinguished career serving the nation and will lead the men and women in the IC [intelligence community] with distinction.”

Trump has not indicated whom he intends to nominate to serve as director of national intelligence on a permanent basis.

Last month, Trump nominated Republican Congressman John Ratcliffe as the next head of the U.S. Intelligence Community. But Ratcliffe withdrew his nomination days later, following growing questions about his credentials and experience.

Many reports have indicated possible nominees for permanent director include Republican Congressman Devin Nunes and U.S. Ambassador to the Netherlands Pete Hoekstra, a former congressman from Michigan.

15.

Hamas: Flying swastikas during protests is ‘exploited’ by Israel

The Hamas call to its people did not condemn what the swastika represents.

By World Israel News Staff

Hamas issued a statement on Friday in which it said that flying the swastika by Palestinian protesters “is condemned and rejected.”

The statement by Dr. Basem Naim, member of the Hamas International Relations Office, said that flying the swastika should be stopped “even if it is done by one person and does not represent the common sense of the Palestinian people. We have to stop similar acts because our conflict with the Israeli occupation is a freedom struggle against the colonial occupier of Palestine.”

The Hamas call to its people did not condemn what the swastika represents.

“The Nazi swastika flag: a symbol of murder and sheer hatred raised yet again at a Hamas riot inside Gaza. In the face of this hatred, IDF soldiers stand alert and determined, ready to defend lsrael today and every single day,” said the IDF statement accompanying the photo.

The weekly Palestinian demonstrations, which regularly turn violent, are part of the “Great March of Return” which Hamas launched in March 2018 on the grounds that it was a protest against U.S. President Donald Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and the transfer of the U.S. Embassy in Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

16.

Rouhani: War with Iran will be ‘Mother of All Wars’

17.

| Report Slams US Troop Pullout from Syria

U.S. plans to keep just a residual force in Syria to ensure the enduring defeat of the Islamic State may be on the verge of backfiring, with some military officials warning the strategy is giving the terror group new life. … |

18.

New IDF team will specialize in hunting terrorists

By Batya Jerenberg, World Israel News

The IDF’s new Special Operations Combat Team successfully finished its first exercise last week in hunting down terrorists, Makor Rishon reported on Sunday.

The special operations group was established after a series of deadly terror attacks over the past year in Judea and Samaria ended with the perpetrators evading capture for days and even weeks.

“It was clear that we had to change our outlook,” one of the team’s commanders told the paper, after the shootings near the Gilad Farm (January 2018), in the Barkan industrial zone (October 2018), and the stabbing and shooting near the Ariel Junction (March 2019) left five people dead and the killers at large.

“Following the attacks, the team developed advanced techniques in cooperation with elite [IDF] units, including those that specialize in undercover work and collecting intelligence,” he said.

According to the IDF, most intelligence gathering – electronic and human – is done by members of Battalion 636. The elite Duvdevan unit is the one that goes undercover into Arab villages.

They work with soldiers currently on duty in Judea and Samaria. But there are others in the group whose identity is still being kept a closely guarded secret.

The intense, two-day army exercise gave the ‘terrorists’ 12 hours to hide.

It tested the new team’s abilities to first reconstruct the attack, and then track the fleeing men, said the IDF. They made good use of security cameras scattered around much of the region and put all their intelligence means into play to search for their targets.

The officer quoted in Makor Rishon expressed confidence that the special unit will catch future terrorists far more quickly than before.

“The minute that everyone comes to the [attack] site under one brain, one commander, the chase is more efficient,” he said in the report.

“The special forces will immediately join the [community’s] first responders and get the information they need. The overlap will be faster and more efficient, and will get us to the critical hours much more prepared.”

19.

Stopping ‘Xenocide’ in the 21st Century

Along with the recent attacks in Pittsburgh, Poway, and Christchurch, New Zealand, the Aug. 3 attack on a Walmart in El Paso appears to have been perpetrated by a lone-wolf murderer espousing genocidal ideologies — but without the means to actually commit genocide. Instead, these solo génocidaires decide to kill as many Jews, Muslims and now, apparently, Latinos as possible.

In the field of genocide research, this is a new, 21st-century phenomenon. We came to terms with large, violent regimes committing genocide during the Holocaust, but these current individuals pose unique dangers because there are few preemptive interventions we can do, and the perpetrators have no respect for the rules of impunity.

Article II of the Genocide Convention, promulgated after the Holocaust, defines genocide as “acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group.” In my 25 years of researching the Holocaust, Armenian, Rwandan and other genocides, there are certain similarities and themes consistent in every mass tragedy: ideology, dictatorial leadership, armed conflict and government perpetration.

The acts of these individual, radicalized men, and the ideologies behind their actions clearly are genocidal in nature, but are perpetrated by one person rather than a government. There are no obvious precedents of lone-wolf génocidaires in Western society. This presents a legal dilemma.

“Creating a term for the horrific acts carried out by these 21st-century génocidaires would be an important step toward recognizing the gravity of these crimes and developing special programs to counter them.”

These perpetrators will be tried under existing homicide laws, but I believe we are seeing a new and different kind of crime — one for which we don’t really have a term.

Unlike international terrorism, a centralized organization with a hierarchical structure does not inspire any of these lone wolves. Unlike other mass shootings such as at Columbine High School in Colorado or the Harvest music festival in Las Vegas, this brand of killing isn’t indiscriminate: The shooters are targeting a particular group of people whom they deem a threat — Jews, Muslims, Christians, black and white. And unlike hate crimes, these acts are expressly homicidal, whereas a hate crime can occur without causing a scratch.

To better understand and eventually confront this menace, we need a word for it. I suggest “xenocide.”

This combines two Greek words to mean the killing of people perceived as foreigners or outsiders. It suggests, rightly, that the act is rooted in racism and xenophobia. It implies the act is fundamentally different from other kinds of killing. It also implies mass killing, because the target is not an individual; it is a group.

It is worth remembering that when World War II began, there wasn’t a word to describe what was happening to the Jews of Europe. The word “genocide,” coined by Raphael Lemkin in 1944, wouldn’t be formally adopted as a legal term by the United Nations until 1946. The term “Churban” came first and “Holocaust” came later.

“There are no obvious precedents of lone-wolf génocidaires in Western society. This presents a legal dilemma.”

By creating a legal term, the U.N. gave the international community a tool for prosecuting perpetrators and ultimately — hopefully — preventing other genocides from unfolding. The word “genocide” also was a way to express an international consensus that this type of killing is a moral abomination.

Creating a term for the horrific acts carried out by these 21st-century génocidaires would be an important step toward recognizing the gravity of these crimes and developing special programs to counter them.

If “xenocide” became an internationally adopted legal term, perhaps penalty enhancements could be brought to bear for perpetrators, along with educational programs, preventive measures and special law-enforcement engagement. And perhaps as a society, we could find a ledge to grab in this ongoing nightmare that has left so many of us feeling like we’re slipping down a cliff.

As UNESCO Chair on Genocide Education, I plan to advance the study of xenocide, so we may develop preventive educational measures. It’s now up to individual governments — in particular, the United States, where xenocide is most common — to begin implementing laws and measures to limit this new phenomenon.

Stephen D. Smith is the Finci-Viterbi executive director of USC Shoah Foundation and UNESCO Chair on Genocide Education.

Liberman sets sights on becoming Israel’s next prime minister

By World Israel News Staff

Avigdor Liberman, head of the Israel Beiteinu party, appears to have his eyes directed at the prime minister’s office, Israel Hayom reports on Sunday.

“I don’t reject the possibility of a rotation at the head of the government,” he said at a Saturday event in Modi’in.

“It interests me to be prime minister, but I’m realistic and try to see the whole picture. I’m trying first of all to bring in enough mandates,” Liberman said.

“The cat is out of the bag. Liberman dragged the state to the insanity of repeat elections only because of his desire to be prime minister. Today, he admitted that he desires to be prime minister in a rotation with Gantz,” the Likud said in a statement, referring to Benny Gantz, a former IDF chief of staff and head of the Blue and White party, which won 30 Knesset seats in April, making it the main challenger to the Likud.

The Likud nevertheless insisted that Liberman does want a rotation and that his recent comments were evidence of his intentions.

Liberman brought down Netanyahu’s governing coalition in November 2018 when he quit as Defense Minister, arguing that the government wasn’t tough enough against Hamas in Gaza.

The Israel Beiteinu leader than prevented Netanyahu from forming a new coalition following the April elections, leading to a second round of elections scheduled for September 17.

Polls show Liberman strengthening in the polls. If accurate, that means he will again have the ability to decide if Netanyahu can form a government or not.

21.

08-05-19

United Nations: Hamas recruits children for terror activity

Guterres notes in the document that one of the UN’s biggest challenges in this regard is preventing the recruitment of minors for terrorist organizations. “Children who work for terrorist organizations are victims,” ??Guterres said. “They are exposed to high-level violence and exploitation that influences them physically and mentally.”

The report detailed the various terrorist organizations which recruit children, including Hamas and Hezbollah. The report confirmed that children in Gaza and Judea and Samaria have been recruited by Islamic Jihad, Hamas and other terrorist groups.

The UN also warned that in Lebanon similar recruitment of children is carried out by Hezbollah, a Palestinian terrorist group called Ansarullah and other terrorist groups. The common denominator of these terrorist organizations is that they act against the State of Israel, most of them openly.

Hamas, among other things, recruits children in the Gaza Strip for its demonstrations on the border during which they are required to throw stones and serve as human shields, an activity officially condemned by the United Nations.

Israel’s ambassador to the United Nations Danny Danon said that “a young generation continues to grow up on violent incitement against the state of Israel under the auspices of terrorist organizations.”

“This is an important step for the United Nations but in order to significantly damper terrorist activity, the Security Council must first recognize Hamas and Hezbollah as terrorist organizations and impose immediate sanctions on them.”

(Photo – Wiki Commons)

22.

Netanyahu Urges UK’s Johnson to Take Stronger Stance Against Iran

By Arye Green, TPS and United with Israel Staff